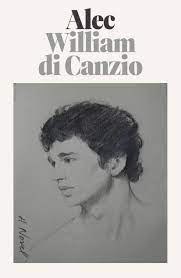

I knew I’d buy this book. William di Canzio’s Alec is a story many readers already know, at least in part. Its inspiration is Maurice by E.M. Forster, a gay romance set in England around 1912 when being a homosexual risked criminal punishment as well as loss of employment and family ties. In the original novel, Maurice Hall fights his urges, even trying hypnosis, but ultimately accepts who he is, falling in love with a gamekeeper named Alec Scudder. Despite differences in class and the challenges pertaining to homosexuality at the time, Forster wrote, “A happy ending was imperative. I shouldn’t have bothered to write it otherwise. I was determined that in fiction anyway two men should fall in love and remain in it for the ever and ever that fiction allows, and in this sense Maurice and Alec still roam the greenwood.”

Forster considered an epilogue but then scrapped it, concluding, “Epilogues are for Tolstoy.”

And, it seems, for William di Canzio. Well, not just an epilogue. Di Canzio takes Alec Scudder and imagines the character’s life prior to meeting Maurice, then offers Alec’s perspective for the events in Maurice before exploring the characters’ lives thereafter. It’s a risky venture to tinker with a classic novel and its beloved characters, but I’m glad di Canzio did so even if I have significant quibbles…which are a given when someone so tinkers.

The Plot

The first section of the book is Alec’s backstory, fleshing out his school days and his work prior to his job on the family estate of Maurice’s friend and former lover, Clive Durham. Alec explores his sexuality with a village chum but, as with Maurice’s dalliances with Clive, the buddy views these as exploratory experiences, what one might do prior to finding a wife and starting a family. Alec doesn’t fight his sexuality. Indeed, he struggles more with the marked differences in England’s social classes, greatly resenting the limits to education and career that come by birth. He does not want to work for others, to bow to them out of obligation rather than, if at all, based on something earned. This storyline complements Forster’s portrayal of Maurice Hall who has some social standing, though limited, perhaps fading. Hall at least has access to a respectable career; in fact, it is his duty to follow the path he too has been born into.

The middle of the novel establishes Alec’s beginnings on the Durham estate, then offers Alec’s perspective upon first seeing Maurice, carrying through until the end of Forster’s story. With some significant exceptions, explained hereafter, this account maintains Forster’s tone. Indeed, as di Canzio notes in the acknowledgments, he obtained permission from the E.M. Forster Estate to use many passages from the original work, weaving in his own writing. This is well done, allowing Maurice lovers like me to revisit the source material while learning more about Alec.[1]

|

| Alec and Maurice, as depicted in the 1987 movie adaptation of Forster's "Maurice" |

As di Canzio takes the story beyond the timeline of the original novel, Maurice and Alec explore the “now what” of their new relationship. Having fallen in love rather quickly, there are practicalities to figure out in a society where the risks are considerable should people see through the subterfuge of Maurice hiring Alec for a business venture and catch on to the true nature of relationship. This begins well with di Canzio introducing new characters, including an established gay couple, Ted and George, free spirits living near a village called Millthorpe. This is a nod to Forster who writes in his 1960 Terminal Note that accompanies Maurice of being inspired by his esteemed friend Edward Carpenter at Millthorpe and his “comrade” George Merrill. It’s a nice touch.

Unfortunately, the fact that events in Maurice end in 1912 means that the sequel portion of Alec coincides with World War I. The characters are separated from one another since England’s classism extends to participation in war as well.

Frankly, war scenes bore me and/or disturb me. Even when a battle isn’t occurring, references to life in the trenches—the cold, the fatigue, the rats—get monotonous. I suspect there’s limited overlap between readers who love gay romance and those who seek war stories. Forster himself recognized this in his 1960 Terminal Note which appears as an afterword in Maurice, stating that his attempts to write an epilogue “partly failed because the novel’s action date is about 1912, and ‘some years later’ would plunge it into the transformed England of the First World War.” I’m with Forster. It’s hard to sustain the story of Alec and Maurice when they are apart for a hundred pages. Perhaps it creates longing and suspense for some readers; for me, it killed the momentum and made me want to get on with it. Knowing the dates of the war, it was maddening to know how much more I’d have to endure when a scene was set in, say 1917. Though tempted, I didn’t skip pages. (That’s what happens when I buy a book instead of checking it out from the library.)

SPOILER ALERT: Thankfully, di Canzio doesn’t stray from Forster’s overarching intention, that being to allow Maurice and Alec to “roam the greenwood” for ever and ever. It would have been sacrilege to do otherwise. My problem with the ending is the clear shift away from Alec and back to Maurice. For a book that sets out to give us more about the life of Alec Scudder, di Canzio does away with all of Alec’s family so that the ending reverts back to Maurice, his sister Kitty and his mother. The final thoughts and actions involve Maurice, not Alec. I suspect an editor may have required that di Canzio tack on his own brief epilogue.

Departures from the Tone of Maurice

I wonder how Forster would have reacted to certain liberties di Canzio takes, straying from the original’s staid demeanor. There’s considerably more swearing which I’m not sure suits the time. While the f-word was around, it would have been rarely spoken.[2] (Even as late as the seventies when I was growing up, it was considerably less commonly used than now. My mother, born at the outset of World War II, regularly complains about viewing options on Netflix. “Why do they have to use that word?”)

|

| Edward Morgan Forster |

While Forster might have objected to some of the swearing, I wonder how he’d have reacted to the somewhat graphic sex scenes. On the night Maurice Hall and Alec Scudder consummate things in Maurice, Forster writes: “someone [Maurice] scarcely knew moved towards him and knelt beside him and whispered, ‘Sir, was you calling out for me?...Sir, I know…I know,’ and touched him.” Sharing a bed is as titillating as it gets. “They slept separate at first, as if proximity harassed them, but towards morning a movement began, and they woke deep in each other’s arms.” Di Canzio’s Alec adds far more to the scene:

Hall locked the door; when he returned, he stood at the foot of the bed, naked, aroused, unsure…The sheet was tangled across Alec’s middle; he pulled it away. Maurice smiled at the welcome…He touched the head of Alec’s cock and showed him the droplet on his fingertip. He wiped it on his own cheek.

Then, as soon as Alec is alone:

When he took off his shirt, he still could smell Maurice. He inhaled deeply, happily. And he smiled when he saw their spunk, dried on his belly and legs, on his chest and shoulders, plenty of it, all mixed together.

What would E.M. Forster think? Considering he didn’t dare have Maurice published until after his death, would he be horrified or envious of this openness in writing? I suspect he’d still favor restraint.

Final Thought

I’m glad William di Canzio opted to write Alec, a companion piece of sorts to Maurice. It’s risky and creates expectations…as well as a built-in readership. There are bound to be disappointments. I’m not fully satisfied with the story, but I appreciated the chance to revisit beloved characters in gay literature.

[1] It’s possible that the seed for di Canzio’s novel comes from Forster’s own prodding. In reference to the character of Alec Scudder, Forster noted, “He became livelier and heavier and demanded more room, and the additions to the novel (there were scarcely any cancellations) are all due to him.” Still, the character challenged Forster. “What was his life before Maurice arrived? Clive’s earlier life is easily recalled, but Alec’s, when I tried to evoke it, turned into a survey and had to be scrapped.”

[2] It’s not that Forster confines himself to “gosh, golly,” “darn,” and “fudge.” In one scene in Maurice, Alec, speaking of Clive’s mother, grouses to Maurice, “Penge where I was always a servant and Scudder do this and Scudder do that and the old lady, what do you think she once said? She said, ‘Oh would you mind kindly of your goodness post this letter for me, what’s your name?’ What’s yer name! Every day for six months I come up to Clive’s bloody front porch for orders, and his mother don’t know my name. She’s a bitch. I said to ’er, ‘What’s yer name? Fuck yer name.’ I nearly did too. Wish I ’ad too.” Still, sparing use of profanity not only reflects the time but adds potency when it appears. In this passage, Alec Scudder is not “shooting the shit” with buds at a bar. His words underscore his abhorrence for England’s entrenched classism.

2 comments:

I was never a fan of "Maurice." Too plodding and obscure and uninteresting. Maybe I need to give it another chance.

"Alec" might be more interesting, although I'm with you on the subject of unnecessarily excessive profanity. But the long WWI section—yeah, not a fan of those either, in movies or books.

I appreciate how this book expands on a beloved story and gives voice to an often overlooked character.

Post a Comment